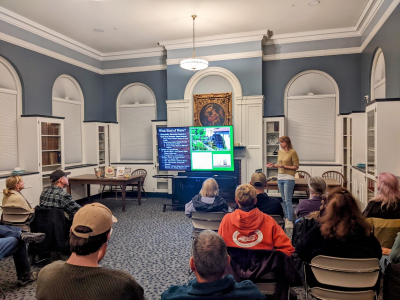

We went back to basics for our most recent Ale Together Now program, exploring how water contributes to beer and how it is used in the brewing process. We tried a variety of delicious samples, exploring how water works behind the scenes to bring out the flavor we know and love in our favorite brews. Join us as we dive into the many ways that water, the main ingredient in beer that is so often overlooked, contributes to our favorite beers!

Water is an incredibly important part of the brewing process, making up 90-95% of a beer. Plus, it takes between 3.5 and 6 gallons of water to make one gallon of beer! Water is used throughout the brewing process-- not only as the main ingredient in the brew, but also for rinsing and sparging, as well as cooling the beer, cleaning the brewing equipment, and in the serving process.

Looking more closely at beer itself, water can impact the flavor, aroma, and mouthfeel of our favorite brews. It also affects the enzyme activity of the beer and impacts fermentation conditions of the wort. Having the right water for brewing is vitally important, so most commercial breweries have some kind of filtration system, which can be adjusted according to which beer style they are making.

The hardness of water impacts the flavor, mouthfeel, behavior of other ingredients, and the reaction of compounds in beer. Hardness is the concentration of dissolved minerals in water-- hard water is mineral heavy, and though it can be hard on equipment, it is great for brewing malty beers, like British ales. Soft water is lighter in minerals, and is great for making lighter styles like pilsners. Calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate ions can affect malt extraction and yeast activity: chloride, sulfate, and sodium ions bring out certain flavors of the beer.

Historically, breweries needed to build near reliable water sources. Locations like Plzen, Vienna, Munich, Burton on Trent, and even Dublin have water sources with varying minerality, and the beer styles that each of these breweries produce are based on the water that they have available. As a result, unique beer styles were produced in different regions.

As an example of how local water affects beer production, lets look at the pilsner-- a golden lager that originates from 1840s Plzen, Czech Republic. Pilsner Urquell, brewed by Plzeňský Prazdroj in Pilsen, incorporated new brewing methods with local ingredients, mirroring trends in Germany. Plzen's water is very soft, with low minerality, low alkalinity, and a low profiled base. This water type allows the subtlety of other ingredients to shine, from the sweet breadiness of the light grain to the clean, crisp finish.

The Burton ale, or the pale ale, is an English style ale from 18th century Burton-on-Trent. It was originally an ale that was malty, dark, and strongly hopped, and it gained popularity with the East India Trading Company because the extra hops helped preserve the beer. Because the water from Burton-on-Trent is high in calcium sulfates, the beer produced there tends to have a higher pH. This works well for hoppy beers, where the sulfates can bring out the bitterness and the calcium can bring out the sweetness of the malts. We sampled Last of Canterbury from River's Edge Brewing Company, noting the hoppy flavor of this English pale ale.

The water in Dublin, Ireland has also shaped the Irish stout into what it is today. The Irish stout was originally an 18th century adaptation of the English porter, with added roasted barley and black malts. Dublin's water is alkaline, high in minerals that add a harsher flavor to the water and making it ideal for dark ales. The acid in heavily roasted malts helps to balance the alkalinity of the water, and the minerals in the water help enhance the malty sweetness of the beer. We tasted Extra Stout from Guinness & Co. from Dublin, Ireland.

Brewers in Goslar, Germany were brewing a tart, light-bodied, wheat-based ale that was similar to a Berliner Weisse, using local water from the Gose river. This water is naturally saline and mineral-rich, and the sodium in the water rounds out the sweet and bitter flavors of the beer. Calcium and magnesium help bring out the sweetness, and promote yeast activity. Nowadays, Gose recipes need to mimic the saline Gose River water-- so brewers tend to add sea salt, gypsum, calcium dichloride, Epsom salt, and adjuncts like lime, cucumber, and coriander to their Gose recipes. We sampled a very interesting Gose from Freigeist Bierkultur (Braustelle) called Geisterzug Rhubarb. This beer featured strong flavors of pine and salt, along with a hint of sweetness and tartness from the rhubarb.

Off-flavors and aromas can come from all aspects of brewing, including the water source. For example, a rotten egg flavor can come from sulfur present in water, and musty flavors can come from bacteria or micro-organisms in water. Astringent flavors come from water that is too acidic, and metallic flavors can come from water high in iron. Good water sourcing and storage practices, along with filtration, can help prevent these flavors from developing.

We are so excited to dive into even more beer styles (and ingredients) with you at our next Ale Together Now sessions. Visit the online calendar to learn about upcoming programs, and be sure to join us for our December Ale Together Now session on Wednesday, December 17 @ 6:30 pm! Don your greatest, and ugliest, Holiday sweater and enjoy some Christmas ales with us as we celebrate the season.

Cheers!